.jpg.transform/extra-large/image.jpg)

Data to the people

Data is the new oil and we’re sharing a lot of it. Here’s how we’re doing it - and why.

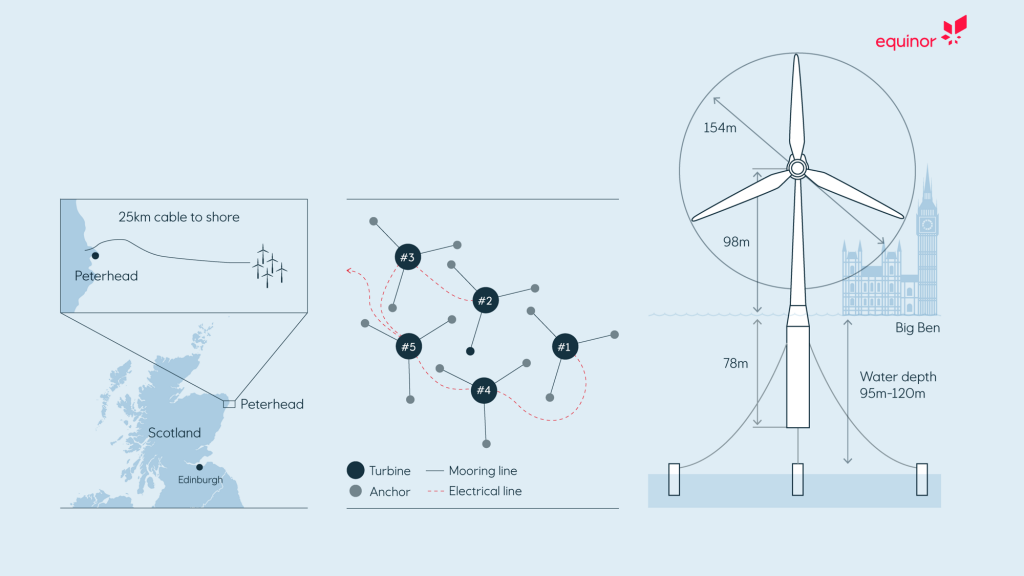

In 2018 and 2019, we released two datasets to the public; the first one a complete set of subsurface data from the Volve field, and the latter data from one of our Hywind Scotland wind turbines. But if data is the new oil, why are we giving it away for free?

We made the Hywind data available in November of 2019 and the set also contains a short memo that describes the main characteristics of the assets and floating turbines, Giovanni Battista Picotti tells us.

“Our objective is to lift the floating wind industry, increase its competitiveness, support suppliers in developing solutions and establish a platform for collaboration."

Giovanni Battista Picotti

For years, academia had requested access to the data to use in research and the Hywind team had long thought it would be useful to create an open data set.

“To make it relevant for analysis purposes, we wanted environmental conditions to be constant throughout the interval. So we looked for representative intervals where parameters such as wind speed and wave loading on the structure were constant,” Giovanni tells us.

“As a lecturer I’m always looking for data to provide to my students and a data set like Volve is incredibly valuable. It’s a little like winning the lottery.”

Anna Marita Braaten, Lecturer in Petroleum, Rogaland Technical College, Norway

A win-win with wind

While Hywind Scotland was the world’s first floating wind farm when it opened in 2017, there are still challenges facing developing floating wind further. Which is reflected in the ways the data has been used.

“There are quite a few examples of the data being used in mooring studies. It’s one of the greatest challenges facing floating wind, both in shallow and deep waters,” Giovanni says.

Moorings keep the turbines anchored to the sea bed and are designed to cope with extreme fatigue loading, which is evident in their significant cost.

“If students, researchers, engineers and designers can get access to real-world data, they can enhance their knowledge, and use it to improve their solutions. This will benefit us in the future: a win-win situation.”

Giovanni B. Picotti

Since the dataset was made available in 2019, they’ve had about 100 requests for access. Scotland-based ORE Catapult handles the distribution of the data sets.

Hywind Scotland dataset

Consists of 11 interval measurements from one wind turbine. Each interval has a duration of 30 minutes. Accessible through the Equinor Data Portal.

Measurements shared:

- Nacelle roll/pitch motions

- Floater roll/pitch/yaw motions

- GPS measurements of surge/sway motion

- Environmental data: Wind speed, Hs, Tp, wave direction for wind sea and corresponding for swell

- Tension in mooring system: All 6 bridles in the mooring system

New life after closing

But our data sharing ventures aren’t just about floating wind. As one of the few companies in the world, Equinor released a set from the now abandoned Volve field in 2017. This set contains everything that happens from the reservoir and up to the ocean surface.

“But the data can be given new value if others, in particular research institutes and vendors, can use them to test, validate, and benchmark new technology, for example related to machine learning.”

Marianne Houbiers

“We will also benefit from this indirectly,” she adds.

The Volve data sharing came when Marianne and Lars Olav Grøvik joined forces. They had been working on sharing data with universities and the industry respectively, and realized the potential in Volve’s data.

While she provided an academic viewpoint, geologist Lars Olav came with a business case: using the data to develop a data transfer standard and integration solutions.

“The data set lets us test this standard and solutions across different companies. Now that we’ve accomplished that, it’s interesting to see the other use cases the data has had,” Lars Olav says.

He tells us that while he knows of data sets that are bigger in terms of volume, he thinks the Volve set is quite unique. It contains everything from raw to interpreted data for the entire eight years it was in production.

“As far as I know this set is pretty unique. If we want to keep moving forward we’ll need more data sets like this one."

Lars Olav Grøvik

Volve dataset

The most comprehensive and complete open shared dataset ever gathered on the Norwegian continental shelf. Accessible through the Equinor Data Portal.

Covers a total of around 40,000 files:

- Static models

- Dynamic simulations

- Well data

- Real-time drilling data

- Production data

- Geophysical data (including interpretations)

- Various reports and more

Open to all

But the data hasn’t just helped students and researchers – it’s also helped our own software development teams. One of them is the seismic-zfp team, who are building an open source library to compress seismic data files.

These datasets are, in the truest sense of the word, simply massive and need to be compressed before they can be uploaded and used in the cloud.

“After we built the open source library, we had to test it on actual data, and the Volve data set was just perfect. It’s a manageable size, but the biggest advantage is that as a public dataset we can test it anywhere we like without a bunch of paperwork.”

David Wade

These enormous amounts of data makes compressing it quite an important puzzle piece to figure out. While large amounts of data are difficult to handle, they’re also costly to store up in the cloud. But when the data set they use to test it is open, why would they make this cost-saving algorithm open source?

“One of the reasons is that if other people have good ideas to improve it, they’re more likely to share it with us. Another is that we can start working with external partners more quickly,” David says.

“I used the Volve production data, well report and reservoir data for my final thesis in college. The data was very helpful in my work.”

Shelty Pheronica Rana, petroleum engineering graduate, STT Migas Balipapan, Indonesia

Learning geological age from bugs

The Volve data set has made its way across the globe and been put to different uses. One of them was the Force ML Hackathon in September 2018. Here, David and his team (from Cegal, Schlumberger and UiB as well as Equinor) took the biostratigraphy data - records of different microfossils that have been fossilized in different layers of rock.

“As evolution happens, you get different species and strata in the rock. You can actually work out how old the rocks are from which organisms you find,” he tells us.

“Thanks to the Volve data, we were able to work in a cross-industry team to produce a machine learning algorithm that could tell us how old the rocks were by which microfossils were present.”

David Wade

If you’re not into rocks you might be wondering how important their age is. The answer is that it’s actually extremely useful!

“Knowing their age means you know where you are in world history. Basically, it’s like having a map of the timeline you’re drilling through and that gives you an ability to understand where the layers of rocks actually go between two wells,” David says.

“I used the Volve data for scientific research that resulted in a peer reviewed article. Data sharing is very important and can help us as researchers show what benefits the industry can achieve with appropriate use of data.”

Tuna Eren, associate prof. Dr., Yakın Doğu Üniversitesi, Turkey

Making development easier

The Volve data set gets around and has also been used by the Heap Purple team working on WellX. They’re building an internal library of reusable components to help visualize wellbores and associates subsurface data.

“During development we need data to experiment with, but at the time the only data we had was classified. That’s always a challenge to work with,” Øystein Lygre tells us.

Øystein has been working on the project since 2019. The data in itself is central, even though they’re working on visualizations of it and not calculations, since visualizations help users gather insight about the data.

“The data set makes development a lot easier for us and it opens new possibilities with open source. We can run demos with real data and share the code with others,” Øystein explains.

“Having the possibility of using real/realistic data while building a visualization tool allowed us to design and implement a tool that’s more effective and performant.”

Andrea Brambilla

The Heap Purple team is also collaborating with the VidEx team in building a reusable component to create intersection visualizations for wells. They’re planning to use the data for testing and demo purposes as well.

“But the Intersection component is open sourced using MIT license, which is incompatible with the Volve license. This means we cannot host the data together with the code, so we are currently looking into a technical solution to solve this issue,” Andrea Brambilla explains.

Has reading this given you any ideas or sparked an interest in the data? Maybe you see something you can use it for? Then head over to the Equinor Data Village to ask for access.

And while you wait, feel free to check out some more stories here on Loop to see more of what Equinor IT is up to. Until next time!

People

David Wade

Lars Olav Grøvik

Giovanni Battista Picotti

Andrea Brambilla

Marianne Houbiers

Øystein Lygre