Scoping out a smarter future

[Python3] [Raspberry Pi] [Phidget]

Ready for the SmartScope saga? What started as a simple idea evolved into a tale of the high seas, with marine life aplenty and a little bit of software ingenuity. Now, it’s making life easier for people at sea.

Try to imagine you’re standing on the bridge of a boat, gazing out at the horizon and looking for whales, seals, birds - mammals of any kind in general. The boat is rocking, the wind is blowing in your face and a biting cold sets in. Now, not only do you have to spot an animal, you also have to know it’s distance. Ever heard of “finding a needle in a haystack”? It’s a little bit like that and takes a lot of knowledge - and work.

“We were asked by Research & Technology to come up with a prototype that could make this job easier,” Pier Lorenzo Paracchini from IT SI Stavanger says.

Listen and watch as Jürgen walks us through the setup and use of SmartScope.

“In the beginning we wanted to create a prototype device mounted on a binocular that would measure inclination and the direction of the binocular. This would then be sent to a data-handling unit to see if it was possible to use that information in order to get a position on nearby mammals.”

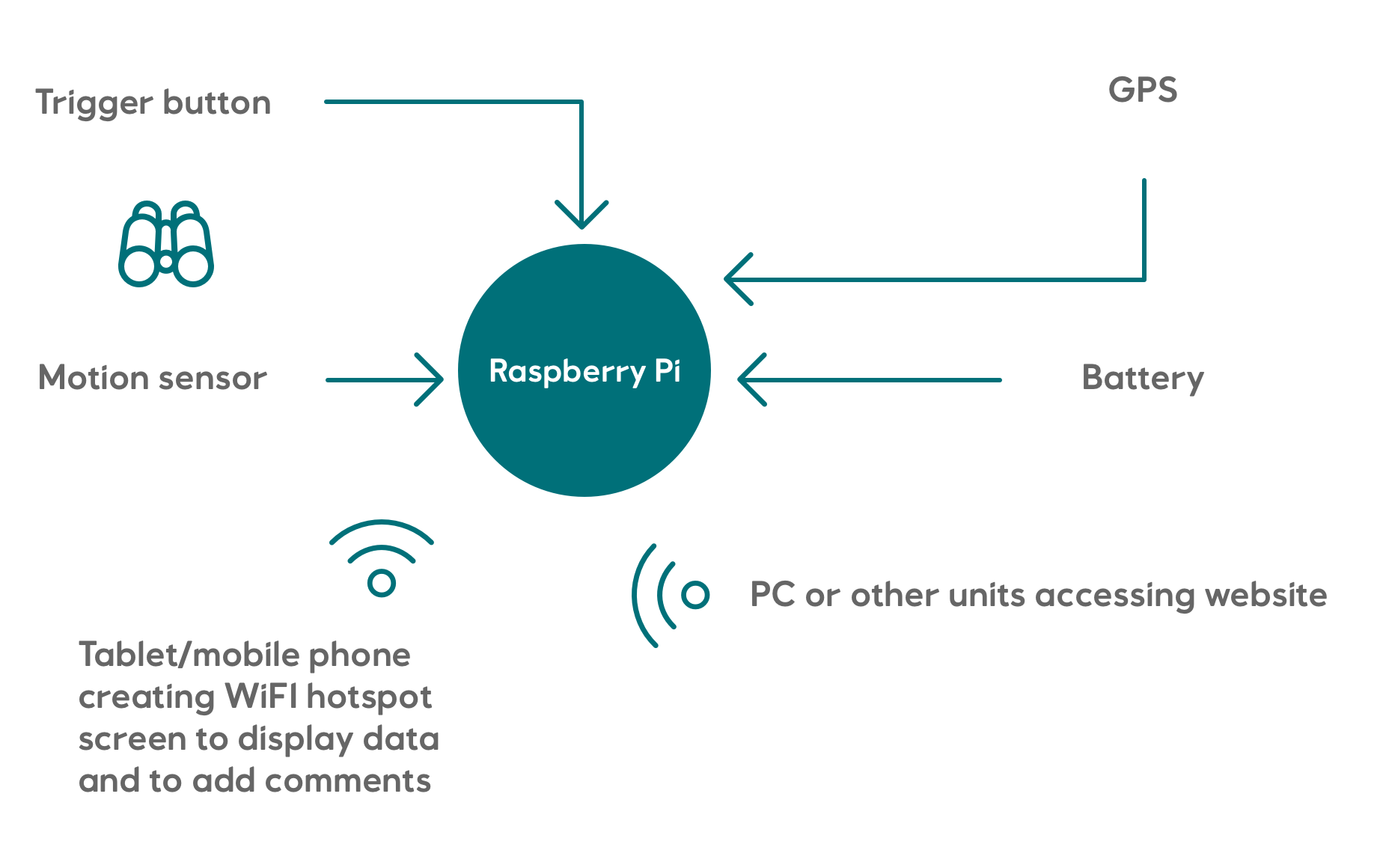

And as fate would have it, they succeeded - and the SmartScope was born. The first version of the SmartScope was built using a single board computer, a Phidget (complete with 3-axis accelerometer, gyroscope and a compass) and various other electronic components through a breadboard. But before we head out to sea at full steam we have to get back to basics.

SmartScope functionality

- Easy to calibrate:

Compass can be calibrated for individual locations to account for local deviations - Easy to use:

Baseline to horizon is calibrated by pressing the Calibration-button. Height of observation point and orientation of motion sensor to be set in set-up menu - Easy to share:

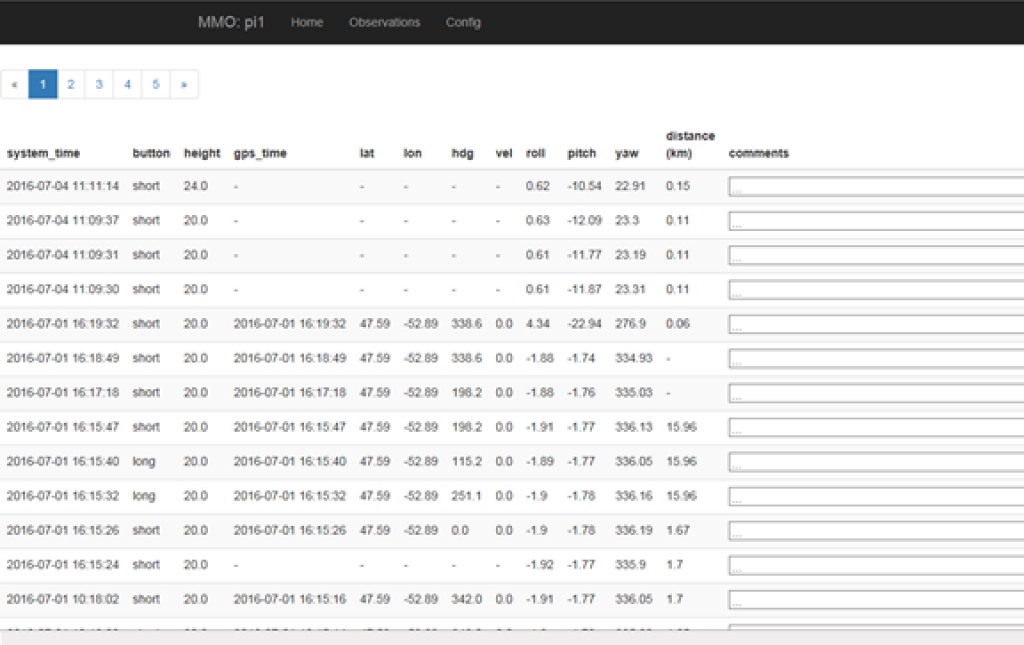

Data can be downloaded in .csv or Excel format for further processing - Easy to save:

Each additional trigger on “measurement” button will save data from motion sensor (acceleration, bearing, motion) and all GPS-data in the Single Board Computer in a new line on the table - Easy to access:

All or subset of data is shown on respective sites accessible via WiFi hotspot. Additional comments can be added on website.

All about the angles

The SmartScope measures an object’s distance from a given point and in our case the object’s are mammals at sea. But why would they need to know how far away a whale or seal is from a boat?

It’s all connected to seismic shooting. Air guns are fired into the depths below and regulations state that no mammal can be within a certain range when this occurs. But to know where the mammals are you’ll need a marine mammal observer or a boat with very expensive sonar systems.

Or - if you have a software team like Equinor - you can make do with a small computer, a pair of binoculars and a gyroscope, all at a fraction of the price of the wildly expensive sonar systems. While it’s name might suggest that it functions using fancy technology only available from a space station, it’s actually quite simple - all it does is measure angles at the push of a button.

How it works

“Using the gyroscope, the SmartScope measures the angle from the horizon to the point you’re measuring together with the height from where you’re standing. Then it calculates the distance to the object you’re looking at,” Paracchini explains.

Together with Harald Wesenberg, Pier Lorenzo spent his playground activity time on the project in its early phases. They tested a Raspberry Pi computer and paired it with a gyroscope, attaching it to a pair of binoculars.

Pier talks about the early days of the SmartScope and the tech behind it all. (Video: Torstein Lund Eik)

Programming meets the physical world

“We weren’t inventing anything from scratch but taking different elements and tried to make them work together. For me, the interesting part was that everything was new and I was eager to start working on it. I had to learn Python as well as the Raspberry Pi to make it all work. The challenge was both in programming and working on a thing you could hold in your own hands,” Paracchini says.

Ultimately, they ended up using a Phidget single board computer for the first versions of the SmartScope - then known as the Durimeter.

In March of 2015 the project was handed over to Arve Skogvold, Asbjørn Alexander Fjellinghaug, Terje Barstad Olsen and Harald Wesenberg from IT SI Trondheim. They had more time available and it was changing from a proof of concept to something that they wanted to create an actual product out of. In the start the team focused on understanding what they wanted to achieve.

“It was a new concept for us so we spent some time on just wrapping our heads around the issue. We weren't meant to spend too much time on it but it was just so much fun it became our full time job,” Olsen says.

“It all felt like a DIY-project since we got so many gadgets and components to build something with. It was very exciting work and a great deal of fun to create something we could hold in our hands."

Terje Barstad Olsen

For someone used to doing programming and not creating anything physical it was quite the change of scenery. One of the challenges they faced was how they could see if the changes they made had the effect they wanted. They couldn’t just run the program and see a result right away, they had to head outside and do a test.

Want to stay updated on Loop?

The man behind it all

We can’t tell the story of the SmartScope without taking a walk down memory lane. The early beginnings of the idea came from Jan Durinck, a marine mammal observer in Denmark.

He knew first hand how difficult measuring distance is at sea, with more than 30 years experience behind him. He pitched the idea to Jürgen Weissenberger at TPD Equinor, who has been pushing the project forward to where it is today.

The difficulty of spotting mammals at sea lies in calculating the animals distance. When standing on a boat and scouting the horizon, you normally have nothing but waves to use as reference points to the whale or other animal you’ve spotted.

Seeing as these waves move around constantly it’s quite challenging to get a correct measurement, which leaves room for human error. You can use a laser but even this isn’t completely accurate, since you can’t be entirely sure you’re aiming at the object you want to measure.

“I approached a couple of electronics companies but there wasn’t a big enough market for it, so I thought it was a project we could promote here in Equinor. We would have to base it on an off the shelf product as there wouldn’t be a lot of money available for the project and we ended up with a Raspberry Pi.”

Jürgen Weissenberger

As it turns out, IT SI were very keen on the idea, eager to take part and it quickly took shape. Weissenberger would do the first tests on his sailboat to see how it would do in waves and he even took the scope hiking, testing it from mountain tops. There is a certain flair of DIY-mentality attached to the whole project - and there still is.

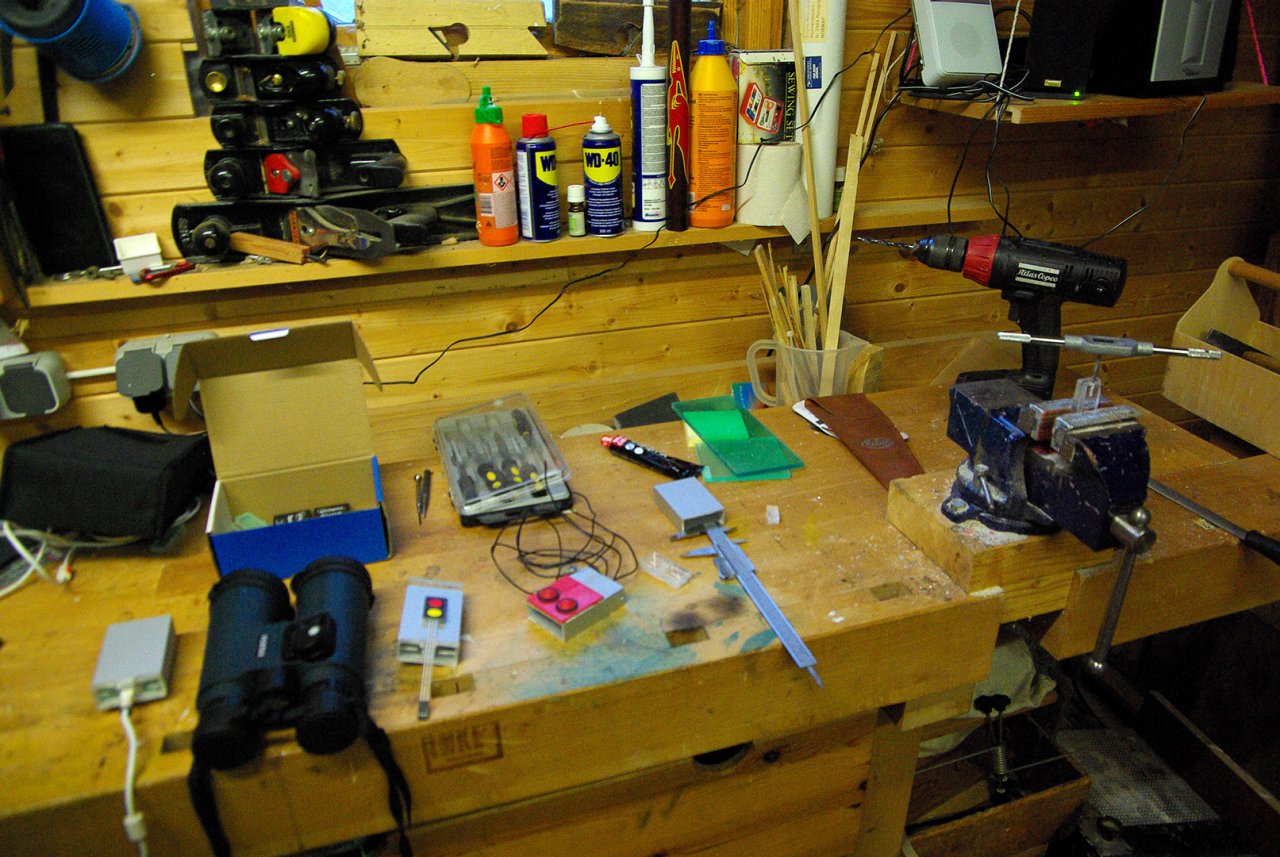

“This might sound strange for such a big company as Equinor but I built the early prototypes in my garage - and I still do! Tom McKeever is also an important contributor. He works at Equinor in Canada, and supports SmartScope deployments in North America.”

The SmartScope came to life in Jürgen's own garage. (Photo: Jürgen Weissenberger)

Investigating an Internet of things

The many rounds of testing proved to be a successful endeavor. During these tests they had several of the ship’s crew showing their interest in the product, as it turns out the marine mammal observers are far from the only ones struggling with measuring distance from a ship.

The first tests were good but a challenge was it’s durability and the single board computers WiFi wasn’t stable enough. The scope didn’t work for extended periods of time, which is crucial when you’re stuck at sea in varying conditions. As such, IT SI suggested a switch to Raspberry Pi.

“After they developed it further and used a Raspberry Pi computer, they tested the SmartScope again outside New Zealand. When they returned, Arve and Asbjørn took the feedback they got and made a integrated circuit board with a button. This meant that you only had to attach the board to the binoculars, and off you go,” Wesenberg explains.

“Working on the SmartScope was a lot of fun. It didn’t feel like work at all!”

Arve Skogvold

Using the Raspberry Pi meant they could run a simple server solution to calculate it all and measuring the height from the user’s position was done through an open source online app. After a couple of iterations they ended up with a pair of binoculars, a circuit board and a working connection with a tablet.

The SmartScope connected with the tablet and the user could write data into an Excel database, and then email it to whoever wanted to use it. Gone were the days of writing on paper.

“This was done at a period of time when we were very curious about the Internet of Things. Since the SmartScope was a wearable device it was naturally very interesting from a software developer’s perspective,” Wesenberg says.

“We wanted to learn more about the concepts and the technology behind it, as well as the challenges that faced it,” he adds.

Hardware

- Binocular with crosshair / reticules

- Single board computer (Rasperry Pi)

- GPS sensor (inside the box) with external antenna

- Motion and magnetic sensor

- USB battery pack

- Button for calibration

- Button for measurements

- Buzzer (acoustic feedback for button action)

- Tablet/mobile phone creating WiFi hotspot

- Headphones to listen to recordings

- All for less than $400 USD.

Breaking the ice

The feedback the team received was crucial to continue working on and improving the device. One of the lucky few who went out on an expedition was researcher Christian Collin-Hansen.

He first traveled to Quebec where boarded the icebreaker Amundsen and set sail for offshore Newfoundland and Labrador Canada. This was done with the first version of the SmartScope, which ran on a Phidget single board computer.

“The device was something Gyro Gearloose could have invented. There were wires hanging off it and small bugs here and there but we managed to solve them and the SmartScope worked exceedingly well all things considering. It was a very fun journey to be a part of,” Collin-Hansen says.

When you're on the high seas and trying to spot mammals in the distance, the SmartScope is of great help.

Breaking your way through the icy wastes outside of Newfoundland and Labrador Canada has its challenges and really put the SmartScope to the test. Collin-Hansen served as a marine mammal observer, alongside two seasoned veterans.

And with a skilled team teaching him the ways of the land - or in this case the sea - he caught on quickly. But he also had a well-prepared set of binoculars with him.

“The main goal of the trip was to see if the SmartScope could be a tool to help ease and improve the work that the observers do. We were absolutely dependent on the SmartScope being robust and user friendly - it had to be a stable system that wasn’t dependant on daily updates. We didn’t have the means to download large datasets from the boat, so this was crucial,” he says.

Collin-Hansen had tested the binoculars before embarking on the ship. Together with Jürgen Weissenberger, the man with the initial plan, he put the SmartScope to the test in the fjords outside of Trondheim.

Working with IT SI was a very positive experience for Collin-Hansen. He was impressed by their curiosity and willingness to learn, which he says was present all the way from the beginning.

“IT SI were able to create a fully functional product in a matter of weeks! It was really fun to see how it went from the early designs to an actual, physical product that we could use and that gave predictable readings with an impressive processing power.”

Christian Collin-Hansen

“We cross-checked the readings from the SmartScope with readings from the icebreaker’s sonar systems and they were very good,” Collin-Hansen adds. But everything wasn’t smooth sailing unfortunately. The single board computer was found to have a little unstable WiFi connections and IT SI recommended a switch to a Raspberry Pi, complete with integrated WiFi, and it’s still the brains of the SmartScope today.

Listen to what it's like to stand outside of a icebreaker ship travelling through the ice offshore of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canda. (Video: Torstein Lund Eik)

Finding a smarter future

Now, the SmartScope gang are helping users learn the tool, getting to know it’s functionality and building the kits. They’re currently preparing the scope for exploration, as they wanted to have a crack at it.

“It’s a very funny project as it’s very low-cost, doesn’t take much of my or the programmers time to set up but the people who use it have a better workday,” Weissenberger says.

He’s not considering it a finished project, it’s quite the contrary - he wants to push it even further. Now, they’re looking at how to put the different electronics into the housing and even implementing a voice recorder so the observer can simply tell the program what they see - and have it put into the logs.

“I would like to provide a full set, containing the binoculars, a computer and a WiFi hotspot. This would let a colleague see and access the protocol lists and logs at the same time,” Weissenberger explains.

“The next generation will be a full set, found in two suitcases. One with binoculars and one with everything else you need to make it easier to use,” he adds.

In late April of 2018, Jürgen handed over two brand new SmartScope kits to a research vessel in Illmuiden, the Netherlands. The crew were heading into Norwegian and British waters to do seismic shooting and will be using the SmartScope. Additionally, two kits have been delivered to a crew heading for an expedition in Nicaragua.

But work on the SmartScope is not done yet, and Eirik Ola Aksnes from IT SI Trondheim has stepped up to the plate and is ready to push the project even further.

“Working on a project that integrates hardware and software offer both satisfying challenges and problems to solve. We rarely get to develop physical products, so working with the Raspberry Pi, sensors and Python is simply a lot of fun!” Aksnes says.

People

Some of the people who have been involved with the SmartScope project:

Jürgen Weissenberger

Terje Barstad Olsen

Pier Lorenzo Paracchini

Eirik Ola Aksnes

Tom McKeever

Harald Wesenberg

Christian Collin-Hansen